Seth Collings Hawkins Explores the Convergence of Public Health and Anthropology to Be a Better Medical Provider

By Pam Davis

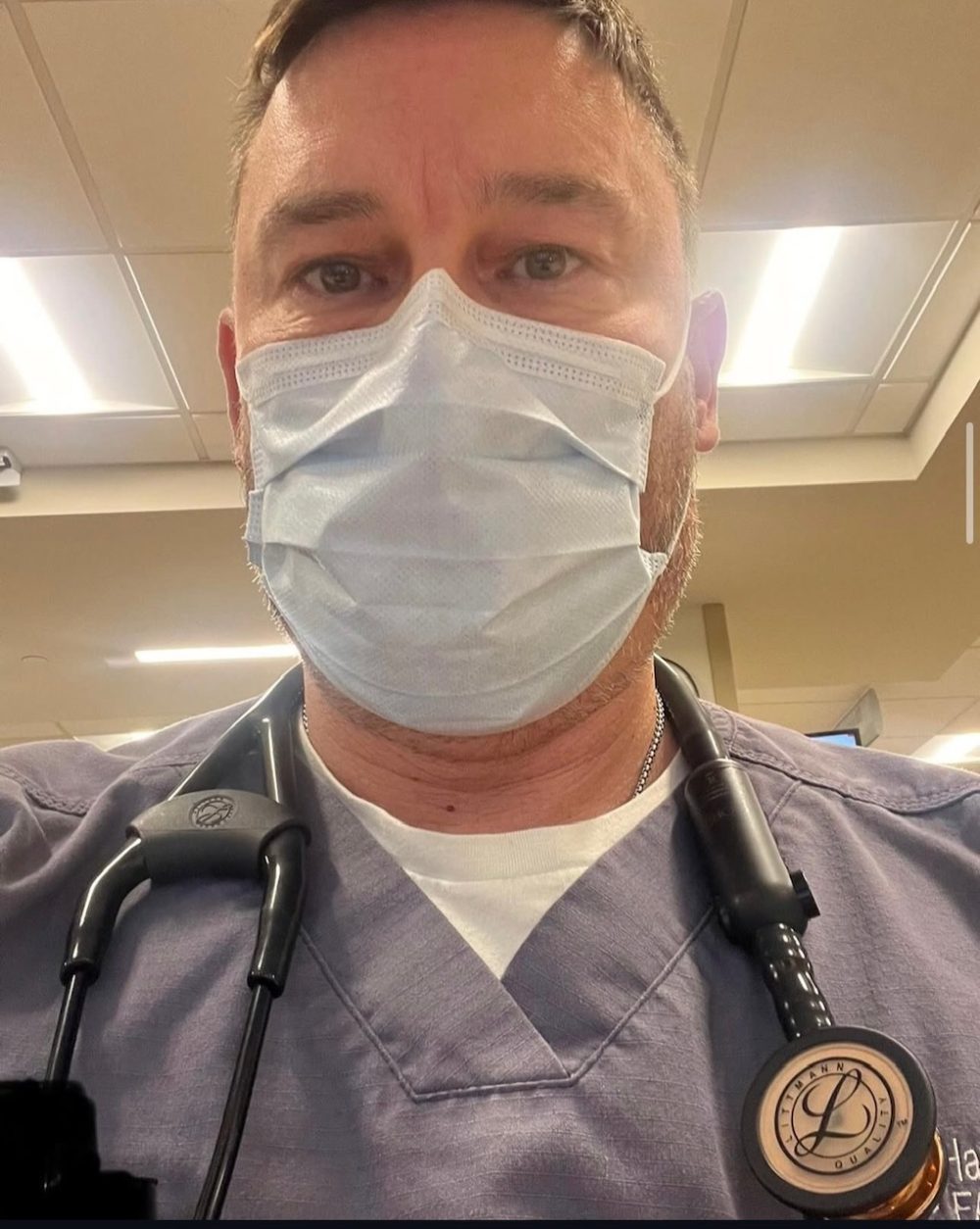

Seth Collings Hawkins, M.D. isn’t your average student. He’s not even your average person.

He’s what you’d call an overachiever’s overachiever.

This guy takes overachieving to the next level and then a few levels above that. And just when you think he’s done, he takes out a ladder and climbs higher up the achievement rungs to see what else is up there.

Don’t get me wrong. I write this with admiration not ridicule. This is a truly impressive guy. His 31-page curriculum vitae tells the full story.

But let me state for the record Hawkins doesn’t think he’s an overachiever (the real ones never do). He’s just doing what he loves, and he wants you to know there have been lots of failures along the way.

“I am the most failing guy you’ll ever meet,” he said. “I have failed at so many things because it’s about the reaching.”

Hawkins received his undergraduate degree at Yale University. He completed his medical degree at UNC Chapel Hill and his emergency medicine residency training at the University of Pittsburgh. He is one of only a few American physicians holding dual board certification in both emergency medicine and EMS and has worked for more than 20 years in wilderness medicine and out-of-hospital emergency medical care. He is the first physician ever awarded the degree of Master Fellow by the Academy of Wilderness Medicine.

Currently, Hawkins serves as an emergency physician within North Carolina’s Catawba Valley Health System and as an associate professor of emergency medicine at Wake Forest University. Since 2011, he’s led the Carolina Wilderness EMS Externship, a program that puts two medical students/resident physicians through intensive training in wilderness EMS tactics and expedition medicine for a month.

While successfully holding a ton of jobs (and not failing at any of them)—emergency and wilderness medicine physician; contract medical director, officer, and adviser to more than 15 organizations; associate professor of emergency medicine; business owner; published author, magazine editor; podcaster; and more—Hawkins applied for the dual Master of Public Health and Master of Arts in Applied Medical Anthropology (MPH/MA) degree at UNC Charlotte. He was 50 years old at the time.

“I began to realize that much more of what I was doing was really public health,” said Hawkins, now 54. “Medical school teaches you to take care of individual patients but being the medical director for state parks or for the U.S. Forest Service or even just for a county EMS system, I was talking about populations of people and how to care for people at scale and I hadn’t been really well trained for that.”

The MPH/MA degree straddles two UNC Charlotte colleges—the College of Health and Human Services for the MPH and the College of Humanities & Earth and Social Sciences for the MA. The three-year program emphasizes the cultural and social dimensions of health and disease in an effort to effectively improve health outcomes.

Going for the dual degree was actually a natural progression for Hawkins who had been an anthropology major as an undergraduate. After 25 years as an emergency physician, he started to think more about the things he learned at Yale—about humans and culture and meeting people where they are.

“I was dealing with one patient at a time and sitting with patients and families and trying to work through sometimes the worst day of their lives,” he said. “I was grappling with their identities and their culture and their sort of place-based cores that they would bring in and lay on my lap and have me help them solve a problem. I realized I was doing applied anthropology as much as medicine; I just wasn’t calling it that.”

Why are you doing this?

Becoming a student again became a masterclass in calendaring for Hawkins who had to juggle his other important roles around classes. He also had to travel about four hours round trip from his home in Morganton, N.C. to Charlotte when in-person attendance was required two days a week.

It was eight hours of driving a week minimum. But this is what he wanted, he said. He chose UNC Charlotte so he could be there in person instead of getting a degree from an online university. But there was a small price to pay: “I think it’s really hard on the body. There are unexpected consequences. Human bodies are not built to be in a vehicle for that long,” he said. “And I learned very quickly, you just can’t do Zoom meetings effectively or safely in the car.”

But the time commitment, driving, and related issues were all worth it to Hawkins who wanted to be on-campus to spend time with other students in person, even when those students were 20+ years younger than him. Though he had no need to hide his age, he wasn’t keen at first on everyone knowing he was a medical doctor. It was a couple months before many of his classmates learned he saved lives for a living.

“I wanted to inhabit the full position of being a student, so I didn’t introduce myself as a physician. I’m happy I did that because I really wanted to be seen as a true peer,” Hawkins said. “I thought it would sort of come out organically. Everyone has a story, and all sorts of people’s stories come out organically. When the information did come out, it was better that it occurred a little bit later.”

There were lots of questions aimed at the newly discovered doctor, mainly why was he doing this in the first place?

“For a lot of people, they are going to use this degree to get their first job and to build a pathway,” Hawkins said. “My reason was that I didn’t know enough about public health. I wasn’t performing the way I wanted to for the medical contracts I had with state, government, and county organizations that were looking to me to be someone who could give them tools. So not having those tools, I went back to school.”

Readjusting expectations

Going back to school came with a few minor challenges for Hawkins.

“It was sobering and probably important to recognize that the cultural metaphors I was using completely landed flat many times,” he said. “Scooby-Doo people understood. Buck Rogers not so much. Most of my fellow students were in their early 20s and I’m in my early 50s. There is a 30-year gap. I don’t even know how to get onto TikTok.”

But even during the disconnection, there was also familiarity for Hawkins. “I have kids. One is entering college, one is graduating from college, and one is two years out from college. Imagine going to school and being a peer with your kids. There’s just a lot of stuff that my fellow students found amusing that I would not know. So that was a bit of a challenge.”

Another challenge for Hawkins was today’s student culture.

“When I was in school in the 90s, there were no computers in classrooms. There were no distractors. You basically showed up to class,” he said. “Now, classes can get recorded and watched later and there can be multiple things you do during your class. Students may be on their computer looking up things or they may be working on things for another class. It was totally alien to me and I had to readjust my expectations for what people would be doing in the seat next to me during a class.”

And don’t get him started on ChatGPT or Artificial Intelligence. Hawkins is a man of many talents, but that kind of technology isn’t one of them—yet. “I don’t know how to use it, but I think it’s something I need to learn,” he said.

When you’re an overachiever, one degree at one time just won’t do so the MPH/MA dual degree was the perfect vehicle for Hawkins. He describes public health as practical and anthropology as theoretical and is transfixed by how they fit so well together.

According to Hawkins, when working towards an MPH, you are learning how to sway minds and advance agendas that involve making the general health of the public better. It’s results oriented. You’re building infographics and learning how to analyze research to create programs and talking about how to change behavior.

This would seem to be antithetical to anthropology, he said, which historically has forbidden the idea of behavior change. “You were not supposed to try to change the people you were studying. You were supposed to explain them to the world and build systems and identify underlying power structures that could explain why the way things worked,” Hawkins explained. “The way that it’s so beautiful to see them working together is that anthropology can problematize the conventions that occur in public health to make it better.”

What stays and what goes

With all that he has going on professionally and all the opportunities his new MHA/MA degree will bring when he graduates this month, what would Hawkins miss most if his focus was to shift?

“That’s a hard question because I’ve seen so many things go away. But they often migrate to something else,” Hawkins said. “Some of the things I get the most satisfaction out of are books and writing. I love the fact that I can get an idea and it’s easier than ever to get that idea out to the world, whether it’s in a book, a blog, a podcast, or something else. I would be really sad if suddenly I wasn’t able to do that.”

Though he’s still able to conduct emergency medicine, he’s not sure how long he wants to stay on that track.

“The medical care in the emergency department is a double-edged sword. I think it’s a young person’s game. Working in the busiest non-trauma center in western North Carolina and being bathed in everybody’s tragedy is just not something you can do for decades and not be affected by it and not have to stop at some point,” Hawkins said.

He’s also affected by those closest to him. In the midst of his many jobs and adventures, Hawkins has a family and soon he and his wife will be empty nesters. “They’ve been a part of all this. I’m really trying hard to not be sad about the next phase and let them go. But I think for all of us who have kids, that’s a very human thing. And there’s a professional element to it in that they’ve also seen all of this and been a part of it. So, even though it doesn’t seem like a professional loss, I think it’s a change of life that would be exceptionally meaningful to this kind of work. And I’ll be sad to see that go.”

Pam Davis is the Director of Communications for UNC Charlotte’s College of Health and Human Services.